I thought I might blog about my diagnosis of macular disease in May 2022, and how things are going after two years.

As I recovered from my first bout of COVID-19 in early April 2022 I noticed something strange in my field of view. When I looked at straight lines, such as the venetian blinds in my studio, those lines looked wavy. There was nothing else apparently wrong at that time. I Googled the phenomenon on the Internet and found articles about 'Wet Macular Degeneration' which sounds frightening and for artists it is.

I booked a consultation with my optician and sure enough she and her colleague confirmed Google's diagnosis. They referred me to the Hull Eye Hospital.

After a couple of weeks I was seen at the Hull Eye Hospital and went into their assessment process, which consists of photographic scans of each eye and letter recognition eye tests for each eye.

I was called in to the eye hospital again after a further couple of weeks, given another set of eye tests and scans and finally a consultation with a senior doctor.

The doctor showed me the scans, before and after, and diagnosed Dry Macular Degeneration (DMD) in the left eye, and Wet Macular Degeneration (WMD) in the right eye. He explained that in my right eye the situation is more serious as fluid is leaking into the retina, causing the distortion of my sight in that eye. He recommended eye injections for the right eye, using an 'anti-VEGF' drug which can combat the rogue blood vessels which are rupturing . He pointed out that my macular disease was not so bad at that time, and that there were risks of infection from the injections. He warned that in some cases of mild macular degeneration these risks can outweigh the benefits of the injections. I decided nevertheless to try injections.

The doctors did not really explain a lot about the mechanics and science of macular degeneration, but I learned a lot about this from the Internet, where there are some good quality sites which give information about the condition. At the hospital I was given a booklet published by a charity called the Macular Society, about AMD (age-related macular degeneration), which explains in a simple way what the disease is.

Overall I am happy with how the National Health Service (NHS) handled my treatment then and since.

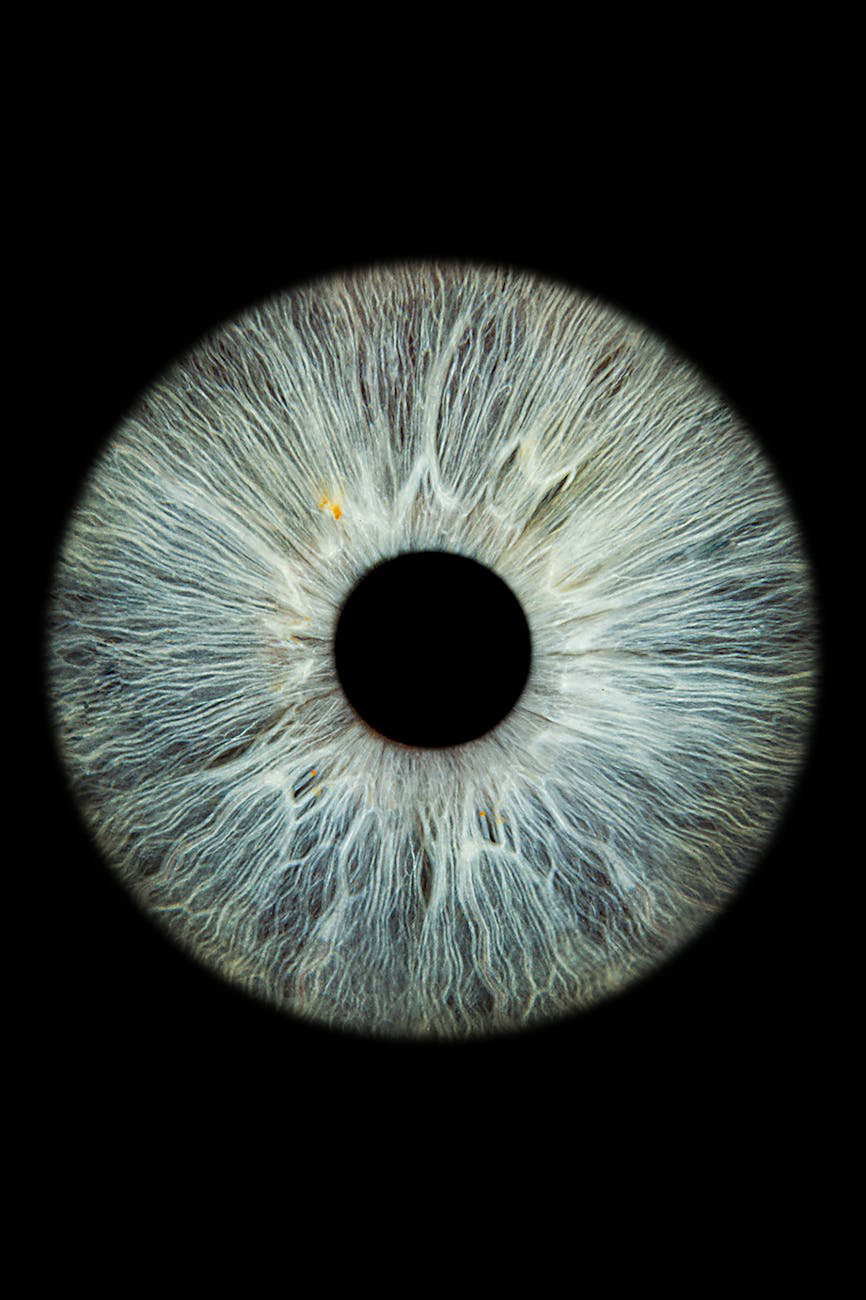

No one really told me what I could expect for my vision in the future but that is probably because this disease progresses slowly for some and rapidly for others but no two cases are the same. I found out from my own research that macular disease eventually destroys one's central vision leaving only peripheral vision. The degeneration generally takes about ten years. Some people are very unlucky and it develops fast, others have it for decades but still maintain good eyesight. The macula is eventually more or less destroyed by the disease - this is a small 5mm wide part of the central retina which handles detail vision, facial recognition and fine colour perception. The ability to watch television, red and write, and use a computer or mobile phone is also severely affected. The rest of the retina is responsible for peripheral vision which allows one to basically see one's surroundings, but not in any detail.

Driving a car is impossible in the advanced stages of macular disease, and already the British DVLA (Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency) has asked me to subject to a specialised eye test. Strangely enough this seemed to test my peripheral vision more than anything else and was obviously aimed at checking the capabilities of drivers who suffer from a range of eye diseases. I passed it, but I will have to resit it every few years. So far so good.

Meanwhile I joined the Macular Society and I recommend anyone diagnosed with macular disease to do the same. It provides online information of a high quality, a magazine and case study videos. It also showcases in its magazine new treatments and gadgets to help aid vision. Also it organises local groups of people who can meet up online or in person to discuss the difficulties faced by those who suffer from macular disease.

I am glad that if I had to suffer from this disease then at least I was 62 years old when diagnosed. Sometimes children are diagnosed and the Macular Society magazine features their stories, which are heart-breaking.

After diagnosis the NHS put me into its system, which is designed to deliver mass health care, and does a pretty good job. Some systems in some countries are supposedly better, but sometimes citizens have to bankrupt themselves to pay for their treatment. I prefer the British system for all its imperfections.

At first I had injections once per month at the Hull Eye Hospital. The appointment takes about one hour and twenty minutes and consists of a number of stages, always the same with every visit:

- Arrive at the eye hospital at the designated time from my appointment letter. The hospital receptionist tells me to wait in a designated area, usually 'E'.

- Wait until called.

- Checking-in by the friendly nurses, to ensure I am who my appointment letter says I am, and that it is the right eye which is being injected, and that I have consented to this.

- Back to area E. Wait until called.

- Eye drops to dilate my pupils, given by the nurses.

- An eye test also given by the nurses where each eye is tested separately against a board of letters, which get smaller as one gets to the bottom. I tend to get 85 for my left eye (100%) and 82 for my right eye.

- Back to area E. Wait until called.

- A scan of each eye by a specialised machine. I place my chin on the chin rest and look into the machine, focussing on the green cross of lights displayed. The scanning technician tells me to blink. I blink and then flash! - the photograph is taken with the help of a small flash of light.

- Back to area E. Wait until called.

- I am ushered by a nurse into a small room where the eye injection will be administered. Usually it is given by a doctor or occasionally a nurse and there is always another nurse there to assist. The nurses place my belongings to one side then put me at ease as the injection is directly into the eye and I know from my online conversations with other sufferers that many are frightened of eye injections. Some refuse to have them at all. Actually the injection is not that bad. I lay down on a medical bed with the upper portion of the body slightly upwards. They place a special membrane over my eye and put a clip in the eye to hold the eyelids open. Anaesthetic and antiseptic drops are administered to the eye to be injected. The other nurse asks me to watch her finger and stay still. The doctor takes a small needle and very carefully injects the medication into the lower portion of my eye, which takes about three to five seconds. I see a transparent jellyfish-like form floating inside my eye for about a minute while the medication disperses. There is no pain. The doctor holds her hand in front of me and asks me how many fingers I see. ‘Five’ I answer. The nurse asks me to sit up and gives me back my belongings. She removes the tag from around my wrist. I thank the doctor and nurse, and the nurse shows me out and I leave the hospital.

- I put on my sunglasses as the eye drops have dilated my pupils for the aforementioned scans so daylight seems very bright. Car lights, even indicators, look positively psychedelic. My vision is blurred in both eyes, and even more in the injected eye for the next few hours.

As I said, this initially was once per month, then every six weeks, then it was due to happen every eight weeks, then every three months and so forth. In other words they would stretch out the injections once the lesions in my eye had dried up. But they didn't. So after about fifteen months they put me back to four weeks, which I think is a symptom that things are not going as well as they could.

The lesion in my right eye still has fluid, and it very slowly grows and spreads after about eighteen months of treatment. My vision in the eye is now slightly greyed out.

This is pretty calamitous for any fine artist. But there is nothing I can do about it. As they say, what will be will be.

[Update 31 May 2024]

The anti-VEGF drug aflibercept (brand name Eylea®), which I was having in my eye injection, had stopped working by March 2024. Therefore one of the young doctors at the Hull Eye Hospital suggested that I was switched to faricimab (brand name Vabysmo®). I had my first injection of this in early April. I can see the excess fluid on my retina is now drying up, though it has left permanent and damaging tide marks. Nevertheless things have improved a lot. I am having another injection of Vabysmo soon in early May so we will see what happens then.

[Update 27th September 2024]

In June I was bending over preparing a painting for exhibition when I had what sufferers call a 'bleed' where an amount of fluid leaked into my eye, presumably from the area affected by wet macular degeneration. This appears in my vision as a very large mostly transparent 3D floater, shaped like a small disc. It moves around in the centre of my eye and disrupts my vision, blurring things and making it more difficult to see small print with the eye. I have not sought to have any procedure to remove this yet, but am thinking that I might, if my doctors think it is a good idea.

Meanwhile the hospital has placed me on 6-weekly injections, which is a good sign that the eye fluid is getting better i.e. reducing overall.